WCW's demise over two decades ago was probably - and tragically - inevitable, despite the company making some incredible achievements in an industry dominated for the prior decade-plus by Vince McMahon and WWE. The late 1990s period of WCW, which had the benefit of being well-documented via the blossoming internet and its myriad wrestling sites, was a veritable rollercoaster.

Eric Bischoff and the red-hot nWo helped launch the promotion, which wasn't that far removed from its territory-era roots, into the stratosphere. Unfortunately for everybody involved, a combination of factors led to it crashing as briskly as it ascended. What was drawing huge television ratings and PPV buyrates in 1997 and '98 was suddenly out of vogue in '99 and beyond, and although fingers often get (rightfully) pointed at the likes of Bischoff, Vince Russo, Kevin Nash, and more, the truth is fairly simple, if bleak: there was so much going wrong by the end, there was no way WCW was going to survive deep into the 21st century.

5 'Hot Potato' Booking

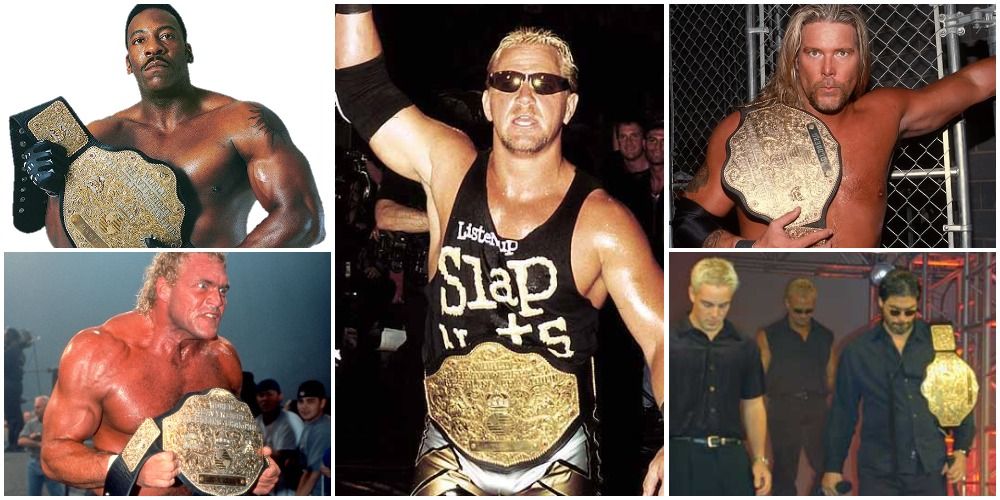

Anti-WWE fans will likely 'whatabout' this point, and they admittedly wouldn't be wrong - both companies were guilty by the late '90s of devaluing their titles - but nobody held a candle to WCW's sheer volume of title changes, particularly with their World Heavyweight Championship. The 'Big Gold Belt' changed hands a reasonable four times in 1996 and three times in '97, but by 1999 and 2000 the title saw 13 and 25 switches, respectively - seven in January 2000 alone!

The idea, it stands to reason, was that the more title changes there were, the more exciting the shows were. This booking style became popular in WWE under Vince Russo, but this was taken to the extreme - increasingly obviously out of desperation. If every night is 'the greatest in the history of our great sport,' then are any? Title changes became a regular occurrence and stopped being special. Even worse, it became legitimately difficult to keep track of what was happening with the titles - if you didn't know who was champion on this week's Nitro, it didn't matter, because it was likely going to change soon.

4 Kevin Sullivan As Booker

Kevin Sullivan is an intriguing character in the overall history of wrestling: he first made his name in Florida in the 1970s, virtually unrecognizable compared to what he'd eventually become. His 'Prince of Darkness' gimmick helped him get over as a heel, and he eventually spent most of his career as a wrestler/manager in Jim Crockett Promotions/WCW. Sullivan got his first opportunity at creative influence in late 1989, as a committee led by Ric Flair including the 'Taskmaster' stymied WCW's revolving door of bookers for a period.

By 1995, however, Flair wanted out and Sullivan was put in charge (under the watchful eye of Senior Vice President Eric Bischoff, of course). His run, aided by Terry Taylor, was generally successful, but he began to lose cache by the end of '98 and was replaced by Kevin Nash (who, despite his claims, definitely booked himself to end Goldberg's undefeated streak). Well-documented chaos ensued, and Sullivan was reinstalled after WCW executive Bill Busch sent Vince Russo home when Russo suggested Tank Abbott win the World Title at Souled Out.

Unfortunately for Sullivan, the company was now in much worse shape than two years prior. Moreover, his promotion was a complication since the man who Busch wanted to take the belt, Chris Benoit, was the same whose baby Sullivan's ex-wife was currently carrying. Benoit, Eddie Guerrero, Dean Malenko and Perry Saturn famously walked out in protest, and although it wasn't Sullivan's fault, per se, the fact is that his booking tenure directly resulted in three of the company's best in-ring workers (and Saturn) jumping ship to WWE.

3 Lost 'Coolness Factor'

One of the most common - and least funny - jokes about AEW has been that it's a "t-shirt company with a television show," which isn't even really an insult (merchandise sales are a good thing). However, no wrestling brand has ever come close to the cultural relevance one simple black-and-white shirt had in 1996-97: the nWo. It's easy to overlook or whitewash now, but in 1996, the New World Order truly felt counterculture. Thanks in part to Kevin Nash and Scott Hall's effortless charisma and the shock of Hulk Hogan's '180' in presentation, the nWo's rise was perhaps the definitive sign that the entire industry was experiencing a new peak in relevance.

For as hip as the brand - and company - were in 1997, however, things were quite the opposite only a few short years later. WWE had easily surpassed WCW in pop culture trendiness, essentially taking the darker, edgier themes the nWo and WCW pioneered and continuing to push the envelope past what Turner censors would allow. WCW struggled to keep up, and after Goldberg's rise to prominence gave the company one last gasp of chicness, desperate measures like bringing back the nWo a million times and attempts to copy WWE just made the entire roster look like 'try-hards.'

2 Run-Ins And Non-Finishes

It's often been said about sports, wrestling and other types of entertainment that breed extremely loyal (and, at times borderline-obsessive) following, but the question remains: how often will fans watch a product that disappoints them - sometimes to the point of active dislike - before simply doing the smart (and sane) thing and simply finding something better to do? The WCW creative team would have been wise to consider this simple fact when writing their scripts: the occasional swerve can be a wonderful tool to keep things unpredictable, but eventually, you have to give fans what they want.

Monday Nitro, especially, saw its popularity at least partially attributable to how often it put its stars on display. The nWo was good for this in particular, as it grew to the point where, in order to maintain (and expand) their power, they'd have member after member run-in at the end of Hulk Hogan title defenses and other moments of peril, saving their proverbial butts and leaving fans dying for their comeuppance. The problem, of course, was that they - and other heels as WCW continued repeating the same mistakes through its demise - needed to lose once in a while. Fans simply became sick of seeing the bad guys constantly win and began changing the channel, especially when they were told outright that a sympathetic favorite like Mick Foley was going to live his childhood dream.

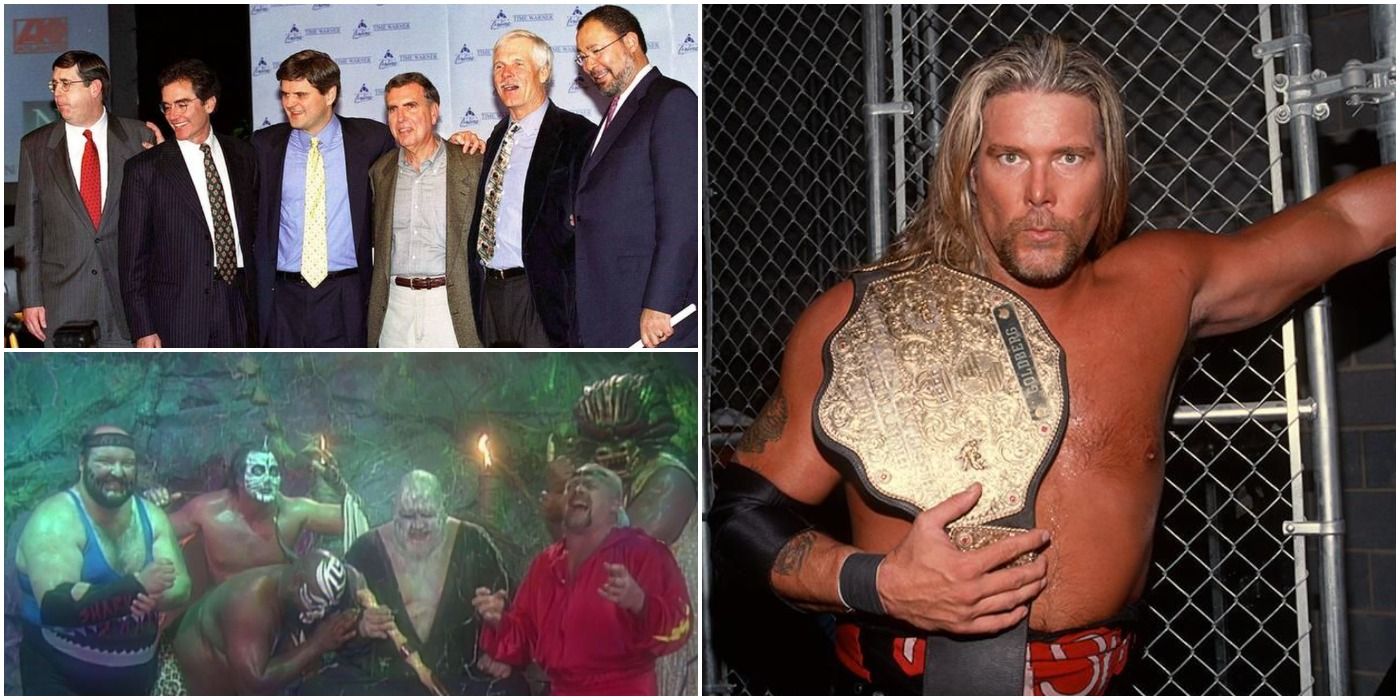

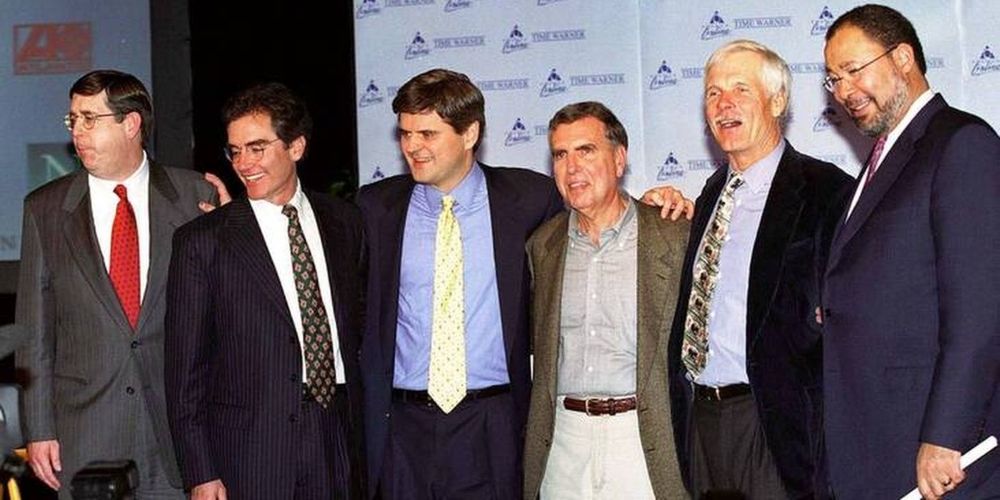

1 AOL-Time Warner Deal

Do these look like a bunch of guys who want to run wrestling programming? Well, the second one from the right - Ted Turner - absolutely did, as the industry was one of the pillars of his fledgling TBS broadcast-turned-cable channel in the early 1980s. However, once the merger between America Online - which then was one of the world's top mega-corporations - and Time Warner occurred, it was no longer up to 'Billionaire Ted.'

Would new top Turner executive Jamie Kellner and the rest of the organization's new 'overlords' have been so quick to cancel all WCW programming in March 2001 if the company hadn't lost $60 million in the previous fiscal year? It's impossible to say. However, most articles, books and documentaries produced in an attempt to analyze and/or summarize what ultimately caused WCW's death cover the Vince Russos, Fingerpokes of Doom, on-air concerts (and subsequent sub-3.0 ratings) and such because, well, they're funny. However, the real reason WCW died is a lot less interesting (and amusing): without a television deal, the brand was essentially worthless. Without Turner's affection for and loyalty to the WCW product and wrestling as a whole, there was no reason for Kellner to not simply wash his hands clean of the somewhat controversial, 'low-brow' product and replace Nitro and Thunder with twenty years of Law and Order: SVU reruns.